- Melody Maker

- June 23,1973

- Courtesy of Linda Crafar

Cat Stevens And A Revolution

In Athens

By James Johnson in

Greece

The shining white block of

the King George Hotel stands imposingly on Constitution Square, Athens. It’s

dauntingly grand in the true sense of the word: a luxurious memorial to rich, idle living

in days gone by. You pass by the comissionaire and into the air-conditioned hum of the

foyer before coming face-to-face with the elderly impassive Greek behind the desk; a man

who surveys his post with an expression moulded to discourage unwanted intruders. I ask

hopefully to be put through to Mr. Georgious’ room and draw little response. The man

continues to look vaguely through his books. Gingerly I mention Cat Stevens, and suddenly

there’s light. A change comes over him. He brightens, smiles and replies in a fair

resemblance of English:

"Oh, you mean Steve

— the singer?"

Yes, that’s right,

Steve — the singer.

Last week Steve the singer,

or Cat Stevens as he’s better known, was in New York Working on the final production

of his new album "Foreigner". This week he’s in Athens, primarily on a

holiday but also keeping a prospector’s eye open for any land that might be worth

investing in. He’s well-known in Athens, at least around Constitution Square, not

only through his records but also for his family connections. Although he was brought up

in London, his family is related to Greece by less than one generation. He’s more

than just another tourist passing through. Why, even the commissionaire at the next-door

hotel turns out to be George, his half-brother. Explains Stevens:

"My father was born in

Greece and brought up a family before coming to London and doing it all over again."

Even though Cat Stevens is

not alone in Athens, it’s still a city that sympathises with the isolate; the kind of

solitary, slightly vulnerable figure that Cat Stevens appears to be. It’s easy to get

lost with oneself along the wide, hazy, heated streets, among the noise and the people. It

only gets you down in the old part of town, the Plaka at the foot of the Acropolis, a

crawling ant hill of cars and tourists, jostling for space among the narrow streets which

house most of the old tavernas. When the temperature is 84 degrees, Cat Stevens wisely

prefers to spend his time in the quieter reaches of the city. He’s not in his hotel

room but out on the Square, a gold crucifix around his neck, a strawberry badge in his

lapel and sunglasses to hide from the afternoon glare. He’s sipping a beer and

talking about revolution. Not in the political sense, a dangerous occupation anyway with

the current regime in Greece, but in a more personal way. He explains how he’s been

through a personal revolution himself just lately and how this has naturally affected his

music and especially his new album, wholly recorded in Jamaica and now due out in the

first week of July.

He feels a change in

himself, partly from being able to escape the pressures of having to keep up his own high

standard in the style which initially established his reputation. He says he’s now

carved himself more freedom, both as an individual and as a musician. His last album

"Catch Bull At Four" was a first step away from the set, determined idea of how

a Cat Stevens album should be. With the new one, he’s made an utterly clean break,

producing himself for the first time, using a different set of musicians and recording it

in Jamaica.

"This is the age of

personal revolutions and that’s when people and things change," he says firmly.

"I want this album to be a shock. I want it to cause some kind of reaction. I

don’t just want people to say 'Oh, the new Cat Stevens album is out this month. Have

you got it?'"

He admits he’s

following a difficult trail, in that he doesn’t want to repeat himself yet can’t

break loose completely.

"I’ve got to

remember my name. I can’t wake up every morning with something new even if I feel it.

But it’s a difficult tightrope to follow. Basically I just want to aim for more truth

with my music. Every time I want to catch that moment when you’re totally open. When

you’re in bed perhaps, with somebody. That moment that if you gain love then . . .

then it’s truthful love." He’ continues: "On 'Catch Bull At Four' I

was searching. Perhaps I’ve now found a truer path with the new album. The last album

had a lot of directions on it and none of them I’ve necessarily followed on the new

one. However, maybe bits of everything may have combined on some of the tracks. I think

it’s important in the sense that I’m allowing more freedom to take place in the

studio. I still love having everything tight and arranged as it used to be, but then that

stops a lot of the flow which is really what I’m after."

This was part of the reason

why Stevens recorded in Jamaica and not as he explained before simply because it’s a

fashionable place to record right now. Instead he wanted to capture some of the

island’s sunny feel. He wanted to make it a summer album.

"The feel tends to

come out in all the music from Jamaica. You know, you can have a bad song, a bad singer

and a bad sound. . . . yet the feel, you know. . . . wow. That’s what I was searching

for, and l found it came naturally."

But didn’t he find the

actual studio set-up and equipment a little sparse and restricting?

"It’s not such a

great studio, admittedly. It’s adequate but there are better studios in England. The

equipment isn’t so sophisticated, which was the only thing I had to fight with. .

." He grins: "That and keeping the bloody piano in tune. You know, it’s so

hot out there everything kept going out of tune. I think the whole album is just slightly

off concert pitch. It’s not noticeable on its own, but maybe if you heard some of it

among other songs it would sound just a fraction tuned down." He moves on. . .

"But the actual recording was very short. We finished in three weeks. The thing is,

they’ve got musicians out there who are paid on three dollars a song so, like,

they’re super-quick: you know, they just rush through it to get on to the next

one."

Stevens also says he

brought in some musicians from New York who he’s admired from afar for some while. It

helped him, as he puts it, to cut the cord. He even parted with Alun Davis.

"Yeah, it was a

complete break. Maybe I should start thinking of another name or something as well."

The most obvious innovation

on the album is the "Foreigner Suite" that takes up the whole of one side. It

came about when Stevens discovered certain songs he’d written seemed to link

together, making it logical to join them up on the album. Also, there’s a song called

"Later" which Stevens describes as encompassing what to him is "the latest

feel — something that’s developed between ‘Shaft’ and ‘Papa Was A

Rolling Stone’.

"You see, I think just

lately I’ve been listening to more black music than anything. I’ve found the

rest rather insipid really. Those guys, though, are not going round any corners.

They’re coming out with the facts as they are. It was a feel I was especially getting

off on when I was writing the number. And it’s an instant number. It might die sooner

than the rest. But I like it for being instant."

In may ways Cat Stevens

seems a complicated individual. He goes to great lengths to explain himself exactly and

sometimes the process can be confusing. He seems to take his life and music on a very

intense level. He admits that he sometimes wishes he could be slightly more spontaneous.

"I love people around

me like that. People who don’t think about it — just do it." he says.

Yet when you ask him what

he thinks is the overall theme to "Foreigner", the answer couldn’t be

simpler. Love, he says, is what it’s all about.

"I’m going

through a very nice experience at the moment that recently has predominately taken up my

mind. I don’t know whether I’m fully in love, but at least I can talk about

it."

Oddly though, his lyrics in

the past concerning chicks often seem written from an unusually removed, objective stance.

He tends to think so himself.

"I think it arose from

the time when I was very young, you know." He tenses his face. "I always

questioned the odds of me turning out to be a girl. Right? And it’s not a question

many people ask. I felt at the moment of conception a fraction of a second might have made

all the difference. And then I thought, well I don’t necessarily claim to be what is

known as a man. I saw these idols like Spartacus and Kirk Douglas and thought I’m not

of that. When I was very young, I never really felt one sex or the other. Gradually I was

brainwashed into thinking I was a fella, but maybe when I write a song or a story about a

relationship, it has many more areas. True emotions. Maybe I see things that aren’t

normally seen."

Stevens says he writes best

when he’s in a lonely or nostalgic mood; when maybe he hasn’t seen anybody for a

day. It all ties in with his image of being a solitary person —a picture of himself

that he feels is accurate.

"If that comes across

then that’s great, because that’s how it is," he says definately. "I

am solitary, I am vulnerable. I am incredibly susceptible to changes. Even the weather

alters what mood I’m in."

But why does he tend to

write in his more insular moments?

"It’s

frustration. To feel lonely is frustration, and it comes out of that."

He admits he writes partly

to discover himself, but adds quickly that he’s lucky to have people to listen to his

music as well. "I think it would be unbearable to live the lonesome life of an

artist, sitting up there in your garrett, with nobody taking any notice of you. That must

be terribly frustrating. He continues: "Now, for me, playing live is what

music’s all about. It’s a thing that everybody enjoys, everybody experiences

together. To me sometimes albums seem a load of crap because live shows are what is a real

experience of music. One day I think it’d be great to go on stage and play an

album’s worth of material that’s never been recorded, and play and then never

record it — just leave it for the sake of live shows. That way it would never get

dry."

He values his previous

albums only for what he can learn from them. That’s the only sense in which he finds

them interesting. He says most of his old songs were fine for their time but failed for

what he’s into now — a more truthful, open approach. I suggest this new way of

thinking may make him more upfront with his lyrics, which in the past have often been a

little understated.

‘Yeah. I think

that’s true. I’m now more able to say something without going round a corner and

then saying ‘ere I am’. I think I’m saying things more straightforwardly

now."

And apart from a certain

lack of faith in albums, for a songwriter and lyricist Cat Stevens professes a suprisingly

low regard for lyrics. He says ultimately his ambition is simply to compose music —

free-form music maybe.

"Your belief has to be

stronger than your words, and music expresses a feeling much more strongly than lyrics.

That’s why I’m writing less and less lyrics these days and more and more

music," he says. One day I’d like to compose music that is untimely because,

musically, that’s as far as you can progress. That’s it. As far as lyrical

progression goes, you can only sing about what you say you are. That’s what I’m

aiming at at the moment — greater truth."

Are there any other

songwriters he feels are working in the same areas?

He thinks for a moment:

"I suppose really Dylan. He got to a certain point and then I think he backed away.

That’s the feeling I got. I thought he was going in completely the right direction,

everything was right. And then I think he became selfish in a way because he started to

say he wasn’t preaching anything which, okay, perhaps again he wasn’t. But I

still think he backed down somehow."It makes it unfortunate because I don’t feel

akin to anybody now because I want to go as far as possible. As far into myself as

possible, as far as possible into people."

His eyes wander round the

square. There are more people around now, as the intense heat of the day gradually

subsides. The traffic sounds softer, more distant, and Cat Stevens feels it’s time to

get back to practicalities. He says he has to get back to his hotel to pursue his

inquiries about the land he’s buying.

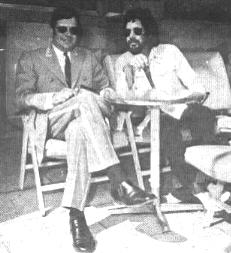

He's a complicated man, a

stark contrast to his half-brother who has now joined us, a simple straightforward soul.

"You know, the family

proud of Steve," says George the Commissionaire, with a pleased smile: "Very

proud indeed."

Cat Stevens and his half-brother

George Georgiou, a pavement re-union in Athens. |